Canine hip dysplasia (CHD) is a developmental disease of the coxofemoral joint, and is a common cause of lameness in dogs. Multiple causes of CHD have been postulated and investigated. Genetics are now known to play an important role in the etiology of CHD. Other factors such as nutrition, environmental influences and hormonal influences however, are also thought to play an important role.

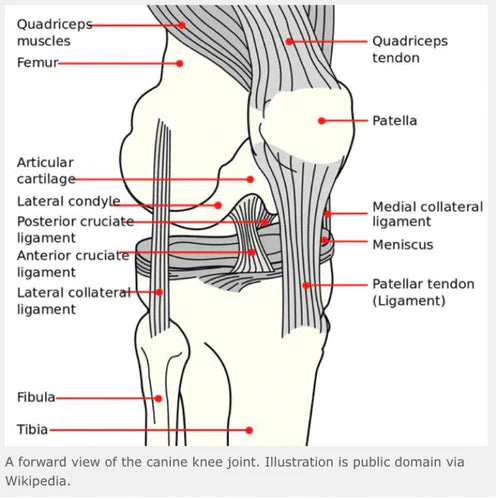

Dogs that suffer from CHD develop an imbalance between the forces crossing the hip joint and the soft tissues supporting the joint, during the development of the musculoskeletal system early in the dog’s life. Joint laxity subsequently develops within the joint and this results in head of the femur subluxating from the acetabulum (cup) during weight bearing (Figure 1). This abnormal movement between the femoral head and the acetabulum leads to abnormal cartilage wear, which is a well-recognized initiator of osteoarthritis.

The majority of cases of CHD are diagnosed in patients above middle age. Unfortunately, however, once osteoarthritis begins, the available treatment options are limited. The goal for the veterinarian is to try to identify and treat hip dysplasia as early in the dog’s life as possible, and this is one area that pet owners play a big part.

Clinical Signs to Look Out For:

Younger dogs in the 3-18 month range typically display more acute signs such as hind-limb lameness, bunny-hopping of hind-limbs (two back legs moving together), reluctance to jump or climb and sometimes decreased exercise tolerance. While the aforementioned signs can be seen in dogs with hip dysplasia, and are relatively easy to detect, the majority of young dogs (especially those less than 6 months of age) tend to have much more subtle signs. The owners should pay particular attention to abnormal gait patterns. The most common, but subtle abnormal gait pattern is swaying of the hips/pelvis (Video 1A and Video 1B) as the dogs walks. Some describe this as the “Marilyn Monroe gait”. The challenge with these patients is that the abnormal gait or the reluctance to perform certain activities is often misinterpreted (both by the owner and sometimes by the veterinarian) as a function of the patient’s age rather than being something abnormal. It is common for owners to attribute an abnormal gait to the patient being “a goofy puppy” or something similar. Educating dog owners, especially those with breeds that are considered at increased risk for developing CHD is important to helping make an earlier diagnosis.

Video 1A&B: This is a 3-month old German Shepherd with severe hip dysplasia. Note how the dog’s hips sway from side to side as he walks. This swaying of the pelvis results in the ankles (hock joint) rotating inwards and outwards with each step. While this is considered a more severe example, the owner should look for similar signs, recognizing that sometimes they are less severe (and this less obvious) than this example.

In the older dog, clinical signs are usually subtler and insidious in onset, often characterized by stiffness after rest, difficulty rising and decreasing exercise tolerance compared to historical norms for that dog. Usually the owner can more obviously discern abnormalities, having past experiences to compare to. For example, the dog use to be able to jump into the truck/onto the bed/couch, or the dog used to be able to go for 2-mile walk, but now cannot. Most owners easily appreciate these changes and bring their dog to the vet for a check-up. Therefore, looking for and recognizing the subtler clinical signs associated with CHD in the immature dogs is critical to allow the clinician to make timely and appropriate treatment recommendations.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis is based on the history, a thorough orthopedic examination and radiographic images. Canine hip dysplasia is seen in a variety of breeds, with large and giant breeds representing the majority of cases. There is considerable variation in the prevalence of CHD between breeds; based on recent Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) statistics for example, 0% of Italian Greyhounds had hip dysplasia versus 72% in the Bulldog.

On the orthopedic examination, your veterinarian will often detect decreased thigh limb muscle mass and pain on manipulation of the hip joint. Specific palpation techniques are some of the best tools the veterinarian has to help diagnose hip laxity, especially in younger dogs. The owner should not be surprised when the veterinarian recommends sedation for your dog at the time of the visit. While this can sometimes be concerning for owners, especially those with young puppies, sedation is safe and the resulting relaxed musculature is required to perform these specific palpation techniques, and to obtain diagnostic quality xrays.

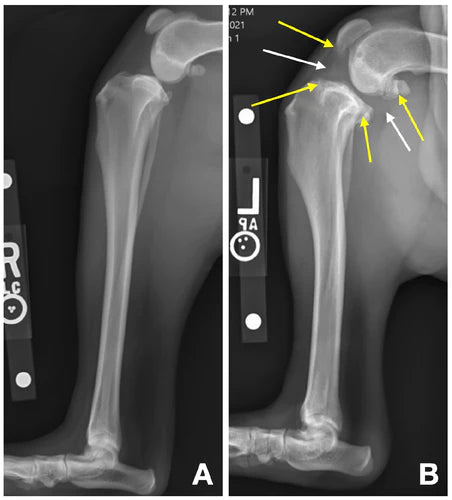

Radiography (x-rays) is a very helpful diagnostic modality, providing information on the presence or absence of osteoarthritis, the severity of arthritic changes and also providing vital information for surgical decision-making and planning, if necessary (Figure 2). There are some specific radiographic techniques and measurements that can be utilized to help the veterinarian assess the amount of laxity in the hip joint. This information can then be used to predict the development of osteoarthritis later in life, and can help guide treatment decision making.

Treatment:

A large number of treatment options have been described for dogs with dysplastic hips. However, research and experience over the years has narrowed down these treatment recommendations to a select few. The choice of treatment depends greatly on the age of the dog, the severity of clinical signs and the magnitude of arthritic changes seen on x-rays.

Treatment options can be divided into two broad categories- medical management or surgical management. In the vast majority of CHD cases, the first line of defense involves medical treatment. The primary caveat to this rule is found in the skeletally immature dog (less than 12 months), where specific surgical interventions must be performed in a timely manner. In the skeletally immature dog, veterinarians have the ability to surgically increase the stability of the joint, giving a chance to reduce the severity or even halt the progression of osteoarthritic changes, thus saving the joint. If your dog is diagnosed with CHD early in life, your veterinarian may discuss performing a juvenile pubic symphysiodesis (JPS)1,2 (ideally in dogs less than 4 months of age) or a pelvic osteotomy, either a double pelvic osteotomy (“DPO”) or a triple pelvic osteotomy (“TPO”)3.

When CHD is diagnosed after skeletal maturity has been reached, surgical treatment options are much more limited and thus medical therapy should always be attempted first. The two surgical procedures your veterinarian may discuss with you are total hip replacement (THR) or femoral head and neck ostectomy (FHO). THR involves replacing the dysplastic femoral head/neck and acetabulum with a prosthetic implant, thereby removing joint instability and the painful bone-on-bone contact4 (Figure 3). FHO involves surgically removing the femoral head and neck, thus removing bone-on-bone contact (between the femoral head and acetabulum) as a source of discomfort or pain (Figure 4).5 The resulting scar tissue formation at the surgical site forms a fibrous pseudo-joint.

Conservative/Medical Management of the Dog/Cat with Hip Dysplasia and Osteoarthritis:

Osteoarthritis, which is sometimes referred to as degenerative joint disease (DJD), occurs in all dysplastic hip joints. Osteoarthritis can be very debilitating to the patient and left untreated can result in an unacceptable quality of life for the pet. Appropriate management of hip dysplasia and the associated OA requires a multifaceted approach (Figure 5). Notice that we do not talk about “treatment” of hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis. The word treatment would suggest that hip dysplasia and OA can be cured. Sadly, no “cure” exists for this condition exists. Despite the absence of any cure, conservative therapy can yield very favorable outcomes in dogs with CHD and therefore should always be attempted before surgery is attempted (exception being skeletally immature dogs – see above). In dogs with CHD, OA will begin developing early in life and it is therefore vital that conservative management is started early in life, with appropriate management continued life-long.

Weight Management

Being at an appropriate body condition is the single most important component of the management protocol for pets with CHD and OA. Weight loss can be incredibly challenging and partnering with a veterinarian or even with a board-certified veterinary nutritionist may help considerably in achieving weight loss at a healthy rate. When considering weight loss, the formula can be made very simple – feed fewer calories and exercise more. Of course, when CHD and OA is at play, especially in advanced cases, exercising can be challenging. Some simple tips that can really help:

- Talk to your veterinarian to determine the appropriate weight for your pet

- Have your veterinarian calculate the appropriate daily calorie intake to achieve the desired weight loss safely

- Try using a weight-loss diet. This can help your pet eat the same quantity as before and feel full/satisfied, all while consuming fewer calories

- Weigh your pet once a week and write it down – otherwise you won’t know if you are being successful

- Slowly re-introduce more exercise and as your pet loses weight

- Cut out the commercially available pet treats- they are typically very calorie dense

- Good low-calorie treat alternatives include:

- Baby carrots ~ 4 calories

- Spinach (1 cup) ~ 7 calories

- Watermelon ball ~ 4 calories

- Pumpkin (1/4 cup) ~ 7 calories

- Ice – 0 calories

Exercise Modification

Notice that this section is not titled “exercise restriction”! A common misconception amongst owners and even with some veterinarians, is that dogs with CHD and OA should be activity restricted, as this leads to less pain and discomfort. Dogs that have CHD are already in a state of cartilage loss. As owners and/or veterinarians we need to do everything we can to protect remaining cartilage and, if possible, permit some cartilage repair. Restricting a pet’s activity because of OA is like a death sentence for the cartilage cells that are already compromised. This is because activity results in joint range of motion. This motion circulates the joint fluid within the joint, bringing nutrients to the chondrocytes (cells of cartilage) and removing the byproducts of chondrocyte metabolism. Cartilage does not have a very robust blood-supply and instead relies on joint fluid for most of its nutrition and metabolic needs.

While we do not typically recommend activity restriction, if the pet is very painful or has an acute flare up of OA pain, it can be helpful to limit activity to leash walks outside for urination and defecation for a period of 7-10 days. Long term, however, joints require activity for proper health and so maintaining a consistent level of activity is key. In general, no activity needs to be prohibited, however, pets are typically more comfortable with low impact activity rather than high impact activities. Activities that are good for the joint include swimming, walking, walking in water (e.g. an underwater treadmill or walking in water at the beach, lake or river-edge). High impact activity (such as running, jumping, playing etc.) causes more concussive trauma to the joints and tends to cause more discomfort. Dogs with CHD tend to most painful with extension of the hip joint- this is why these patients are often reluctant to climb or jump. Therefore low-impact activities are preferred as these will limit hip extension, thereby reducing joint flare-ups and the associated pain. Regardless of the activities performed, of more importance is that activity is provided on a regular (ideally daily) basis. As mentioned already, joint health requires joint movement. If the pet is activity restricted all week long (e.g. when owner is at work) and then the pet goes to the park for an hour on the weekend, a flare-up of joint pain is predictable. This is obviously not good for joint or cartilage health.

Physical Therapy:

Dogs with CHD lose a lot of muscle mass in the rear limbs (Figure 6). Formal physical therapy can play an important role in regaining lost muscle mass and strengthening muscle mass. In many cases, strengthening and restoring muscle mass and working on hip range of motion can significantly improve the quality of life for the pet. It is worth discussing this with your veterinarian or veterinary physical therapy specialist. Often times they can show you a plethora of strengthening and conditioning activities that can then be performed at home.

Pain Management

In order for patients to be comfortable enough to be active, their pain must be adequately managed. The long-term goal in treating CHD and OA is always to have patients on the least amount of medication possible. Working on weight loss and improving strength with low impact activities often will enable us to decrease the dose, or frequency of giving oral pain relievers. However, with flare ups, high impact activity, or when CHD and OA is first diagnosed, treating consistently with a pain reliever for a period of 1-2 weeks can be very helpful.

If the pet can tolerate it (no systemic illness, no liver or kidney issues), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is often the first choice for pain management. When NSAIDs are used long term, screening bloodwork should be performed by your veterinarian every 4- 6 months to determine if any side effects are occurring, or if new systemic disease is developing that may preclude the continued use of an NSAID. While NSAIDs are often the first-line defense for pain control in pets with hip dysplasia and OA, there are many other pain medications that have a better safety profile, that can be also be given (either with NSAIDs or alone). Two of the most common medications used are Gabapentin and Amantadine. It should be noted that some of joint supplements (see below) can also be helpful in controlling pain. Your veterinarian can help determine an appropriate pain control protocol for your pet, recognizing that what works for one pet may not be as efficacious in another.

Supplements:

There is a plethora of different joint supplements available for both people and pets. It is easy to get overwhelmed when deciding what, if any, supplements your pet should be on. Sadly, for many supplements, marketing has gotten ahead of the science and appropriate studies have not been performed to assess their efficacy. In the USA there are no FDA regulations on supplements and therefore manufacturers do not have to meet the label claim- i.e. oftentimes the supplement does not contain the ingredients listed on the label.

For me, in order to prescribe and promote the use of any medication or supplement, that product should be backed up by appropriate scientific research. In my personal opinion, many supplements are overpriced and do not offer a good return on investment. Most joint supplements contain the building blocks of cartilage for example chondroitin and glucosamine. The theory behind their use is that when taken orally, these substances will be absorbed, transported to the joint and converted into new cartilage where cartilage loss has occurred. The evidence supporting that this actually happens however, in people or in pets, is scant at best. For this reason, I do not regularly prescribe these types of supplements.

Another type of joint supplement is one that aims to protect the cartilage that remains in the joint (as opposed to purporting to help build new cartilage). Intuitively, this treatment approach makes much more sense to me. The primary supplement category that works in this way is marine based oils. Arthritis literally means inflammation (“itis”) of the joint (“arth”). Marine based oils are rich in Omega-3 fatty acids which are natural anti-inflammatories and thus when used regularly can reduce inflammation in the joint and thereby even reduce pain levels. Their use can also result in reductions in the dose or frequency with which we need to administer NSAIDs. Furthermore, marine based oils are very safe with minimal to almost no side effects. Personally, I have been using Antinol for a number of years now and this is my marine oil supplement of choice. Antinol is a patented supplement derived from the New Zealand green-lipped mussel. It is rich in Omega-3 and other essential fatty acids. I have seen profound improvements in many patients with OA after starting Antinol. Antinol is also backed up by university-based research that has proven its efficacy in patients with OA; in fact, 90% of dogs with OA improved within 4 weeks of starting Antinol!

Monitoring Dogs with Hip Dysplasia and OA

If your veterinarian opts to manage your dog’s hip dysplasia and OA conservatively, it is vital that the success of this management protocol is assessed frequently. Some dogs respond very favorably to conservative management, long term, and never require surgical intervention. However, some dogs do not have an acceptable response, while other dogs only respond for a period of time before the signs of disability and discomfort return. So how do we know if conservative therapy is successful?

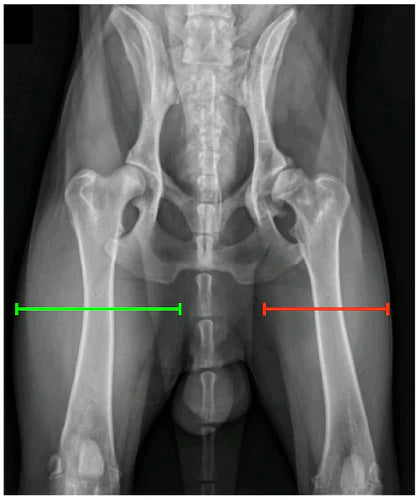

Firstly, your veterinarian should keep notes of the orthopedic examination findings and can refer back to previous visits to make comparisons. One of the most useful tests to assess the efficacy of the management protocol is to take repeated measurements of thigh muscle circumference. This should be done in a systematic and repeatable fashion so that measurements can be compared from one visit to the next. Ideally measurements should be performed at the top of the limb with the measurement taken using a Gulick’s Tape Measure (Figure 7) perpendicular to the limb. The Gulick’s Tape Measure ensures that consistent pressure is placed on the tape, thereby eliminating variation that could come from the tape being wrapped too tightly or too loosely. While most pet owners prefer to avoid surgery, they should be prepared to change course and move towards surgery if necessary. While the veterinarian can help with the decision making process, ultimately your pet will let you know if conservative therapy is working. If you think your dog’s quality of life is adversely affected and/or that they are in pain, then clearly more needs to be done, and if appropriate conservative therapy has been attempted, this typically means surgery is the next step.

References:

- Patricelli AJ, Dueland RT, Adams WM, et al. Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis in dysplastic puppies at 15 and 20 weeks of age. Veterinary Surgery 2002;31:435–444.

- Vezzoni A, Dravelli G, Vezzoni L, et al. Comparison of conservative management and juvenile pubic symphysiodesis in the early treatment of canine hip dysplasia. Schattauer GmbH, ed. Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2017;3:267–279.

- Guevara F, Franklin SP. Triple Pelvic Osteotomy and Double Pelvic Osteotomy. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2017;47:865–884.

- Peck JN, Marcellin-Little DJ: Editors. Advances in Small Animal Total Joint Replacement. 2012:1–273.

- Harper T.A.M., Butler J.R. Hip Dysplasia. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2017;47:807-821.

Figures:

Figure 1: Ventro-dorsal pelvis radiograph of a skeletally immature dog with bilateral hip dysplasia. Normally there is a good ball-and-socket joint between the femoral head and the acetabulum. Here the right hip is subluxated (in the direction of white arrow) from the acetabulum (white dotted line). The left hip joint is also abnormal. Notice how the acetabulum shape and size does not match that of the femoral head (yellow dotted line). In this left hip, there is mild joint subluxation.

Figure 2: Ventrodorsal x-ray of a normal dog’s pelvis (A) and a dog’s pelvis with hip dysplasia (B). Notice the large bone spurs (AKA “osteophytes”) above the cup (solid white arrows) which are not seen on the normal pelvis (solid yellow arrows). Additionally, there are bone spurs along the femoral neck and head (dotted white arrows) which are not seen on the normal pelvis (dotted yellow arrows). Notice also how the normal femoral heads are spherical in shape and they fit into the cup very well whereas the dysplastic femoral heads are irregular in shape and do not sit inside a cup like in the normal hip joint.

Figure 3: Ventro-dorsal pelvis x-ray of a dog with a left sided total hip replacement. The original acetabulum, femoral head and femoral neck have been replaced with a prosthetic cup and femoral head/neck.

Figure 4: Ventro-dorsal pelvis x-ray of a dog post right sided FHO. Removal of the abnormal bone prevents painful bone-on-bone contact. Over time the patient develops false joint (“pseudo-joint”) made up of dense scar tissue.

Figure 5: Management of osteoarthritis (OA) associated with hip dysplasia requires a multi-faceted approach to yield optimal outcomes.

Figure 6: Ventro-dorsal pelvis x-ray of a dog with left sided hip dysplasia (the left joint is on the right of the image). Notice how the thigh muscle mass of the right side (green line) is much larger than that of the left side (red line). A guide to the success, or lack thereof, of medical management of CHD lies in the monitoring of thigh muscle bulk and whether it is increasing (success) or decreasing (failure) over time.

Figure 7: Gulick Measuring Tape. The handle contains a spring and when loaded to the correct tension, a marker ball is seen. This informs the user that sufficient tension has been applied and the measurement should be recorded at that point.